Forging Techniques, Processes, & Finishes

Forging Techniques And Finishes

Blade Construction

Discover the craftsmanship behind our knives in this section, where we explore traditional and innovative methods like Honyaki, Kasumiyaki, and more. Learn how each technique enhances blade performance and aesthetics.

Blade Construction

Honyaki

Honyaki knives are forged using one type of steel for single or double- bevel knives. Traditionally, made of high-carbon steel, now they sometimes are made of stainless alloys. These mono-steel knives need to be differentially heat treated, the same as applied to traditional Katana (Japanese swords). Differential heat treatment allows for the spine of the blade to cool at a slower rate. This produces a softer area which absorbs shock and provides structural integrity, while maintaining a very hard cutting edge. A special clay is used to insulate the spine and is applied in an artful manner, therefore producing the Hamon. It takes a very skilled smith to achieve this properly. The clarity of the Hamon line may be revealed by polishing or acid etching. Forging Honyaki blades and implementing the Hamon takes a tremendous depth of understanding. The blade-smith must fully know steel, temperature, timing, amount of clay used, tempering, quenching and hardening. It’s no wonder that knife- smiths claim the spirit of the blade lies within the Hamon. Since Honyaki knives have such high hardness, they are brittle and prone to chipping if misused. They do have incredible edge retention. It does take much more skill to sharpen as compared to Kasumi knives.

Blade Construction

Kasumiyaki

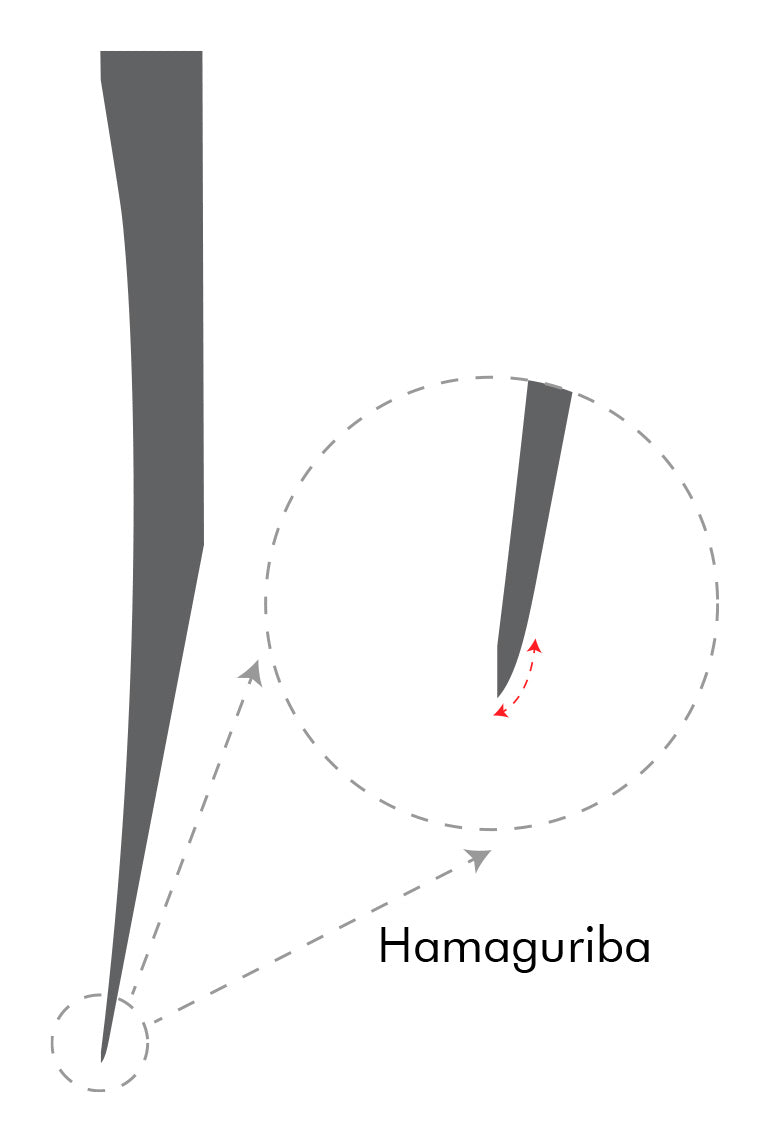

Kasumiyaki is a technique of forge welding hard steel (Hagane) on the back side of the blade with a softer steel (Jigane), on the spine and face of single-bevel knives. It is commonly referred to as Kasumi and less commonly as Nimai (two layer). When further steps in tempering and heat treating are added, plus very high-quality steels are used in this cladding process, this higher-grade is referred to as Hongasumi. The soft steel provides structural integrity and shock absorption, while the hard steel performs as the cutting edge. The word Kasumi literally means “mist” in reference to the hazy appearance of the soft steel contrasted against the glossy hard steel. This wavy lamination line where the two steels meet is beautiful, somewhat resembling a Hamon line. Kasumi knives are easier to maintain and sharpen, but have shorter edge retention.

Blade Construction

Sanmai-Awase

Sanmai-Awase is a method of cladding (applying one material over another). Sanmai literally translates to “three layers” and Awase is Japanese for “cladding”. Commonly called Sanmai, this technique is used for double-bevel knives. Its “sandwich” construction allows for a hard steel core to function as the cutting edge while the softer outer layers add structural integrity. This gives the knife better edge retention. What sets Sanmai apart from Warikomi is that the softer laminates are forge welded to the sides and not applied to the spine. Just as with Kasumiyaki, the lamination line is visible and resembles a Hamon.

Blade Construction

Warikomi-Awase

Warikomi-Awase is similar to Sanmai in that it has a hard steel core and a softer steel jacket. Likewise, this method is used for double-bevel knives. What is different with Warikomi, is the process. The hard steel core is inserted into a split soft steel, then forge welded, wrapping around the core. The hard steel does not extend fully to the spine. As mentioned with Sanmai, the hard steel core performs as the cutting edge while the softer jacket gives the knife structural integrity and better edge retention. Once again, the lamination line is visible almost resembling a Hamon.

Blade Construction

Suminagashi

Suminagashi, globally known as Damascus, is the method of forge welding two or more parent steels. The blade will exhibit the attributes of all the components. Soft steels for flexibility and resilience. Harder steels for toughness and edge retention. Steel ingots form billets which are then hammered, forge welded, folded again and again, creating up to hundreds of layers. The flowing water-like pattern of Suminagashi received its name from the ancient Japanese art of paper marbling of the same name, literally translated to “floating ink”. The information here is simply an overview, since Damascus has a long history. Its origins came from India around 300 BC, and continue to evolve today. Modern Damascus is produced in a wide variety of patterns. In today’s market it is common for Japanese knife-makers to use Suminagashi steels within Kasumiyaki, Sanmai and Warikomi techniques. For example, smiths clad a core of AUS- 8, or VG-10 in Damascus. The wavy pattern can be accentuated by acid etching and polishing. Not only is this beautiful but it performs at a high- level.

Forging Techniques And Finishes

Heat Treat: Normalizing, Annealing, Quenching & Tempering

After the steel has been forge-welded (or not, if it is Honyaki), stretched, hammered and brought to a rough shape, it is ready for heat-treatment and refining the shape.

Normalizing

Annealing

Quenching

Tempering

Forging Techniques And Finishes

Stamped Vs. Forged Vs. Stock Removal: Which is better?

We believe a more appropriate question is “What is better for the user?”. We don’t believe in absolutes, and for this topic, advancements in modern metallurgy and improved manufacturing techniques have blurred the lines. There is such a broad range of people who use knives, from home cooks to professionals. The work required of them is also broad. Other considerations such as budget, skill set, and personal predilections will play a part in making an informed decision. Generally and historically, it was widely accepted that forged knives are very high quality and stamped knives are lower quality. That’s not always the case in today’s world. It’s possible to purchase a quality knife that functions well that is stamped. We suggest that no matter what ‘level’ you choose, purchase from reputable brands & companies. This will ensure you buy a quality product that lasts for years to come. Stock removal can produce very good knives, but takes less expertise in shaping compared to forging.

Click Below To Learn More About Each Technique

Forged

Forged knives are made from a billet of steel by heating the metal in a forge or furnace until it is glowing, then hammering the steel into shape on an anvil. The hammering & shaping can be done by hand, machine (power hammers & hydraulic presses), or a combination of both. A blade can be forged from a single billet (mono steel), or from multiple layers which are forge-welded together, producing Sanmai or Damascus forging constructions. Steps are then taken to aneal, quench, and heat-treat the blade. The blade and tang are then refined by grinding or sanding, attaching a handle, then sharpening.

Stamped

Stamped knives are made by cutting out the shape of a knife from a sheet of steel using a cutting die, laser, or water jet. Typically, multiple knives are cut at once. Very much akin to a cookie cutter. The stamping process never allows for an integral bolster since the sheet of metal is thin. When a knife is forged, the blade-smith can choose to shape and hammer a bolster into the design. Little to no grinding and refinement is required for stamped knives before heat treatment. Handles are attached, then final sharpening is implemented.

Stock Removal

Stock Removal is simply removing away material from steel bar stock. Makers will use a myriad of tools such as files, grinders, belt sanders, saws, or abrasives. Essentially, carving out the thickness, bevels, and shape of a knife, as opposed to forging a billet into shape. It is important to note the distinction of a maker versus a blade-smith, since less skill is required for stock removal. Although, to produce a high quality knife by stock removal, it’s critical that the maker has a good working knowledge of metallurgy to accomplish a high-level of annealing, quenching, and heat treating (thermal cycling). A deep understanding of overall design and balance will further help produce a quality product. Stock removal is a great way to get into the art and science of knife making and smithing.

Forging Techniques And Finishes

The Finishing Touches: Blade Finishes

The knife is now ready for the final stages of sharpening, polishing, engraving, and handle assembly. Blade-smiths carefully watch each step along the way, ensuring confidence that their knives perform without fail. These traditional techniques and processes combined with passion and artistry, produce the world's finest cutlery.

Japanese & German bladesmiths have perfected their craft through the generations. Undoubtedly there are parallels in the making of knives. However, with such differing cultures, Japanese and German knives have some distinct differences in their finishes. —some rustic and some refined. Some intended for a purpose and some only for aesthetics. Some knives might have more than one finish and can be applied to any blade construction. Nowadays, German and Japanese knife makers have influenced one another. It is common to see these designs and influences in knives from both German & Japanese manufacturers.

Click below to read more about each style of blade finishes.

Learn Center

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

!